![]()

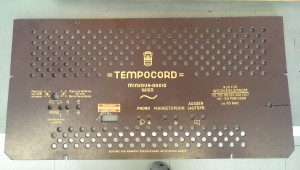

A multi-band radio receiver from the year 1957 is the Tempocord of the company Minerva. The company Minerva was founded in Vienna in 1919 and began in 1924 with the production of radio receivers. The radios were initially made under the name Radiola or Aeriola. It was not until 1926 that the receivers were built under the name Minerva. The name Minerva was used until 1972.

Technical Data:

-

Manufacturer brand: Minerva-Radio Wien

-

Model: Tempocord

-

Construction year: 1960

-

Typ: Radio receiver (postwar receiver)

-

tubes: ECC85 ECH81 EF89 EBF89 EM81 EABC80 EL84 EZ80

-

Operating principle / construction: Superhet receiver IF 480/10700 kHz

-

2 NF stages . 11 FM circles and 6 AM circles

-

wavebands: longwave, medium-wave, shortwave and ultrashortwave

-

Supplyvoltage: 110V, 130V, 150V, 220V, 240Volt

-

Speaker: dynamic permanentmagnet-ovalspeaker

-

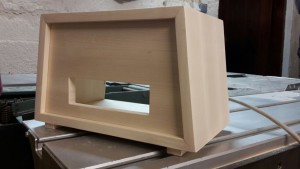

Wooden housing with dimensions: (BxHxT)55 x 32 x 25 cm

(sources: wikipedia)

(the device was provided for documentation purposes by: Berti)